A little over a year ago, a friend from my search and rescue team told me about a hike to a plane crash up in the White Mountains. I’ve been trying to get there ever since, but life and weather kept constantly getting in the way. Yesterday, my patience paid off because it could not have been a better day to get out and explore. Instead of just sharing a few photos with some tips and tricks about how to get there, I’ve gone down a rabbit hole reading about the history of the airline, the crash itself, and I tried to find out about what happened to the crew after, to no avail. Several news articles, court summaries, Civil Aeronautics Board accident investigation reports, and a notebook full of my scribbles later, I’m ready to write up a quick blog post about my hike.

On the morning of November 30, 1954, a DC-3A traveling at approximately 150 knots crashed into the southern side of Mt. Success, just a mere 100 feet from clearing the summit. Northeast Airlines flight 792 had seven souls onboard- three passengers and four crew.

Northeast Airlines started in 1931 as Boston-Maine Airways (or often, Boston & Maine Airways) before eventually becoming Northeast Airlines in 1940. The airline was founded, in part, by Amelia Earhart until it was eventually acquired by Delta Airlines on August 1, 1972.

“In 1939 Boston and Maine established one of the first pilot training courses in the United States at Burlington, Vermont. This resulted in a request from the federal government just prior to World War II for assistance in operating a national defense program for the training of advanced flight instructors. Boston and Maine fulfilled the request and trained many instructors who later became the pilot nucleus for today’s commercial aviation industry.”

from a 1972 Northeast Airlines employee booklet

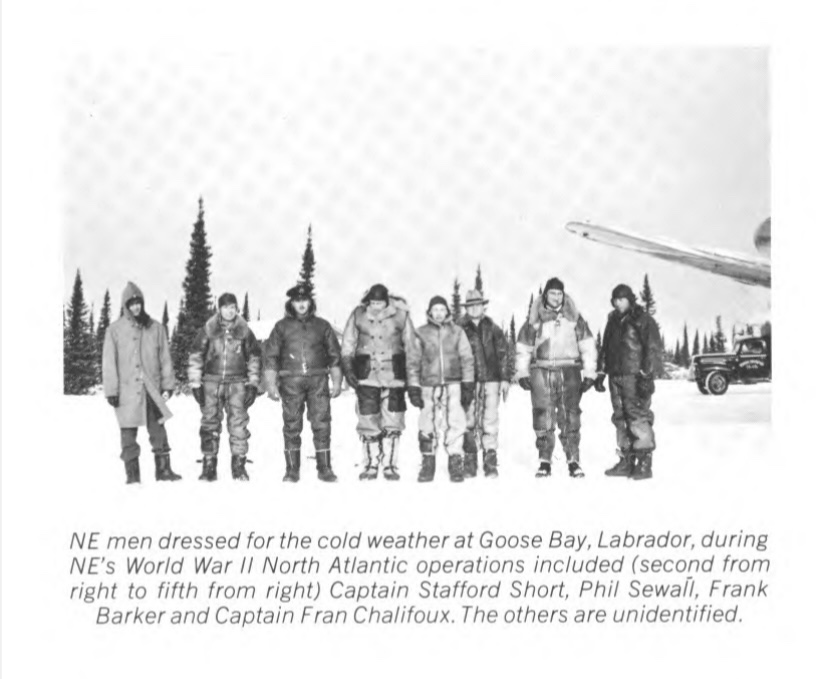

Northeast Airlines pilots flew the Army Air Transport Command flights to Newfoundland, Greenland, Iceland, and Scotland. They were the first to explore the Arctic airways which eventually went on to become commercial airline routes to Europe after the war. The Northeast Airlines radio department established and operated the navaids and radio stations in the Arctic for this to be possible. The book “Island in the Sky” was written by Ernest Gann and later turned into a John Wayne film about these pilots up north.

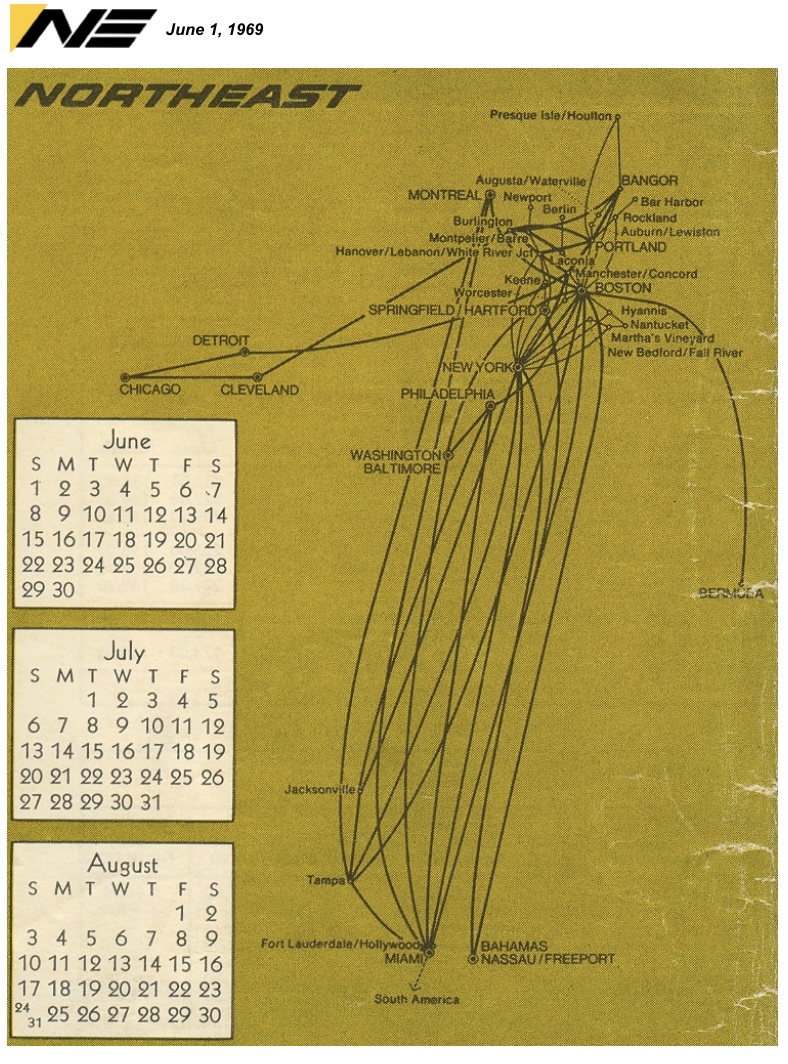

Over the years Northeast Airlines grew and became one of the first US airlines to offer pure jet service with the Boeing 707 and the first airline to operate the 727-200 in 1967. The fleet became affectionately known as Yellowbirds because of the yellow and white livery. Eventually Northeast Airlines started running into financial trouble and battled to maintain its route system to Florida. For a brief period, Howard Hughes had acquired the airline, but the Civil Aeronautics Board continually denying Florida routes led to him selling as he could no longer keep covering the airline’s losses.

After a botched merger with Northwest Airlines, Northeast Airlines was acquired by Delta Airlines on August 1, 1972. This merger is how Delta got into the Boston market.

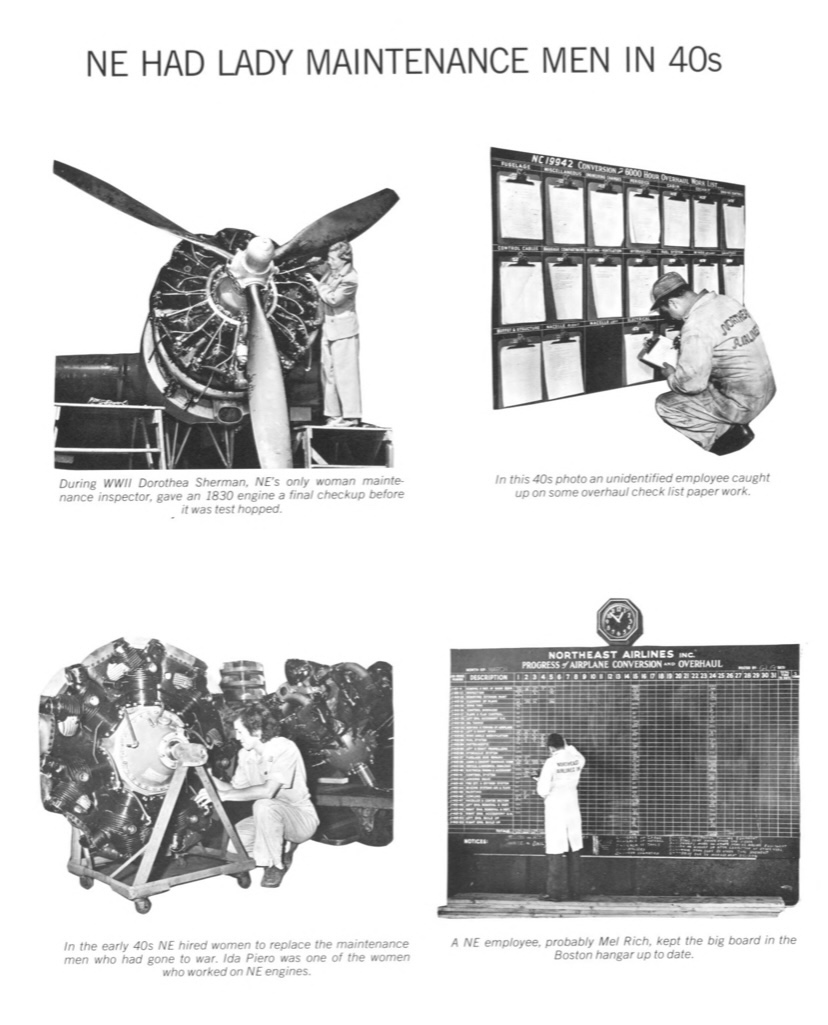

On July 31, 1972, the day before the merger, Northeast Airlines gave out a 66 booklet to all its employees titled “A Pictorial History of Northeast Airlines 1933-1972” which can be found deltamuseum.org.

Over the years, Northeast Airlines struggled to maintain its image due to several deadly crashes around New England, which one might argue ultimately lead to the airline’s demise. One of these crash sites can still be found in the Mahoosuc Range of the White Mountains in New Hampshire- Northeast Airlines flight 792.

On the morning of November 30, 1954, a DC-3A traveling at approximately 150 knots crashed into the southern side of Mt. Success, just a mere 100 feet from clearing the summit. Northeast Airlines flight 792 had seven souls onboard- three passengers and four crew.

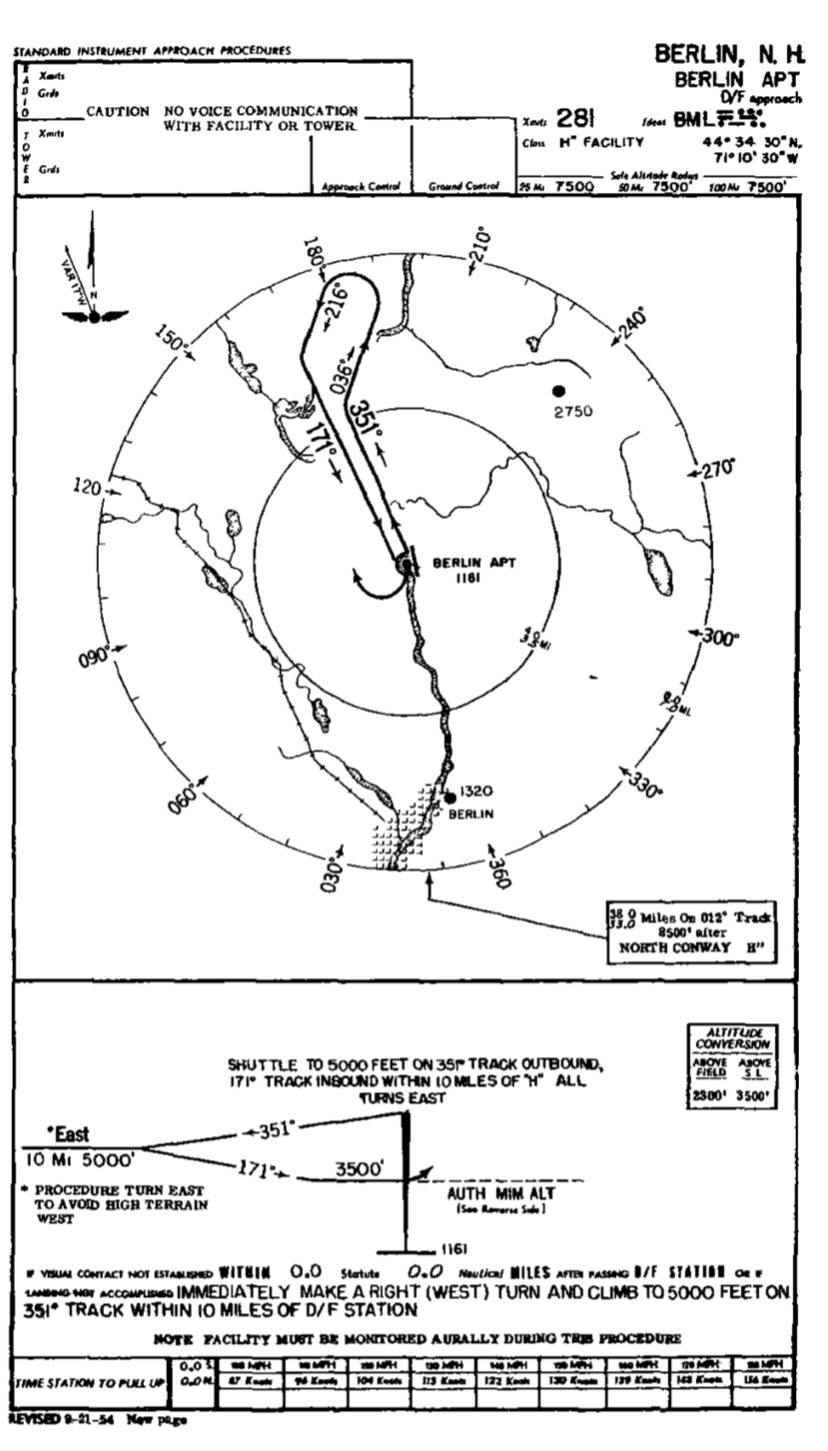

The Douglas DC-3 plane, registered N17891, was scheduled to fly from BOS to BML via CON and LCI on that Tuesday morning. The first two legs had operated more or less on time and were uneventful. They picked up an IFR clearance from CAA’s ARTCC shortly after the 10:39 takeoff from Laconia. “Boston ATC clears Northeast flight 792 for an approach to the Berlin airport via Blue 63 to cruise 8,000 feet.” These words would later be misunderstood or completely ignored by the pilots on their descent to the airport.

At 11:03 the crew called the station in BML for a weather report. They replied with an observation from 10:45 that the ceiling was 3,000′ overcast, 2 1/2 sm visibility, with light snow showers. The weather minimums for the approach into Berlin required 2,300 foot ceilings and a visibility of 2 miles. The flight crew failed to reply with their altitude and position, but acknowledged the weather report. Shortly after, at 11:10 the station agent made a special weather observation to the crew adding that there was now a scattered layer at 2,300 feet with wind out of the northwest at 10 knots and snow showers to the north. There was no further contact with the flight crew after they also acknowledged this weather report at 11:12. About halfway between Laconia and Berlin was a company-required reporting point over North Conway which the crew also failed to provide a position report.

At approximately 11:15 flight 792 crashed into Mt. Success. Onboard were Captain Peter Carey, co-pilot George McCormick, flight superintendent John McNulty, stewardess Mary McEttrick, and the three passengers, James W. Harvey, William Miller, and Daniel Hall. All seven people initially survived the crash, but George and John eventually passed away about two hours later due to injuries sustained from the impact.

The left engine caught fire during the crash and everyone rushed over with food trays full of snow for hours to extinguish the flames.

Around 11:30 ATC suggested a return to LCI due to broken ceilings dropping to 1,500 feet and visibility dropping to 2 miles, which was below the minimums for the approach. Without being able to receive any replies from the flight crew, search and rescue was soon deployed.

Search efforts both on the ground and in the air were thwarted by the snow squalls and low ceilings. The surviving passengers and crew huddled together for the next 45 hours in temperatures below freezing. They used curtains, seat cushions, cabin insulation, soundproofing material, and anything else they could find in their suitcases to keep warm. All they had to eat were a few crackers, cookies, and some tea they brewed over a fire.

Two pilots in an Apache cruising at 7,000 feet that day heard about the missing aircraft and reported that they had seen a DC-3 descend below them while they were about 11 miles southeast of Berlin.

The next morning on December 1, captain Carey was able to successfully transmit a message after trying several frequencies and different wiring of radios before the battery died shortly after. He reported that the flight went down about 5 miles northeast of the field on a hill, but never got a reply. He marked this location on an aeronautical chart, but after the weather improved and he looked around, he quickly realized he was wrong about his estimated location that he had sent out in hopes of a rescue.

Another Northeast Airlines DC-3 spotted stewardess Mary McEttrick waving a flag on the morning of December 2nd. She had been given the nickname “Merry Mack” by the passengers for keeping everyone’s spirits up during those days awaiting a rescue. Mary would eventually continue on as a flight attendant for Delta for many years to come and passed away in 2015.

A doctor was airlifted to the scene to treat survivors and then they were each airlifted out one at a time. CAA investigators were also airlifted to the summit of Mt. Success for immediate on-site investigation of the crash.

During court hearings in 1957, Carey testified that he believed the faulty ADF reversed prior to reaching Berlin, which resulted in him descending below 8,000 feet several miles before the station. He also stated that when ATC issued “cruise” instead of “maintain” he interpreted that to mean he could descend at pilot’s discretion. Part of his defense was also that the Berlin approach plate failed to show 8,000 feet as the minimum altitude. Finally, he claimed that mountain wave turbulence caused them to descend 500 feet, which was partly corroborated by passengers testifying they hit turbulence just prior to the crash.

Despite Carey’s defense, the trial examiner found little to no evidence to support many of his claims. The instruments of the aircraft, including the ADF, as well as those at the ground station, were sent to labs and found to be working properly. The CAB could not understand how a captain with 7,900 hours of total time and 5,500 of those in a DC-3 who had previously flown several times into Berlin could argue a descent below an MEA of 8,000 feet before descending for a procedure turn. Flight 792 possibly crossed BML at approximately 5,500 feet before the procedure turn or Carey attempted a straight-in approach based off his local knowledge of the surrounding terrain while attempting to descend below the overcast layer. Either way, when the airplane hit the mountain, it impacted at an elevation of 3,440 feet, approximately 9 miles to the right of course.

The CAB found the probable cause of the crash “a premature and unauthorized instrument descent to an altitude that did not permit terrain clearance.”

In reading through several testimonies and reports, no matter which way Carey tried to justify what happened, flight 792 descended well below any safe altitude trying to land at BML. Whether flying the full procedure turn with a faulty ADF, a misunderstanding of the approach plate itself, mountain wave turbulence dropping the aircraft 500 feet, or attempting to get below a layer for a straight-in, crashing into a mountain at 3,440 feet shows that they had descended too far. Following ATC’s advice with a return to LCI, where weather was better, or climbing back up to 6,000 feet to get above the clouds would have saved co-pilot George McCormick and flight dispatcher John McNulty’s lives.

To hike to what remains of N17891, you can get to the summit of Mt. Success on Success Trail via the Appalachian Trail (Mahoosuc Trail). I highly recommend doing the short loop to The Outlook for some stunning views. The wreckage is about a half mile past the summit after passing “a large boulder the size of a refrigerator” and dipping to the left down a herd path through the forest. The last part is quite a bit of bushwhacking. I was constantly getting caught and scratched by branches on my way down, but eventually the trees opened up at the crash site. Pieces of the engines, the wings, and the aft section of the aircraft are scattered around. I spent well over an hour just looking at the torn pieces of metal strewn about, trying to make sense of it all. I kept trying to find what remained of the cockpit and nose section of the plane by hiking further down the steep, slippery mountain, but eventually decided I needed to start heading back to my car at the trailhead before I got hurt. If anyone finds the nose section, if it’s even still there, I’d love to know where it’s at. Rumor is that they pulled up and landed relatively flat with the nose only slightly accordion-ing back upon impact. With all three men up in the cockpit initially surviving the crash, I’d imagine it wasn’t in entirely terrible shape. The CAB report stated that the aft section was on a heading of about 350 and the nose broke off to the right, so that’s where I ventured off for a bit with no success. 😦

Lots of people attempt this hike to Flight 792 without being able to find it, and I entirely understand why. The trail up to the summit itself is very wet, goes through lots of muddy bogs, and is rated as difficult. Then, you have to keep going even further through the woods off-trail to find the DC-3. While I wouldn’t personally rate the hike as difficult or even all that technical, I lucked out with a warm, dry day and still did not feel entirely comfortable with my footing for most of the hike. It was a slog both ways, but mostly because of how slippery the trail was. I highly suggest bringing poles for better balance. The only time I had to use my hands was during one brief scramble up and down a large boulder near the summit and while venturing off to find the cockpit of my own accord. The hike to the summit and back is roughly 7 miles round trip with an elevation gain of just over 2,000 feet. Adding flight 792 to the hike brought my total mileage to over 8 miles and 2,300 feet of elevation gain. I budgeted 6 hours for my entire day on the trail for all breaks, a quick lunch, and exploring the site, which worked perfectly. I started shortly after 0900 and got back to my car just before 1500 with my moving time being just under 4 hours. It was a long day with a 3.5 hour drive each way, but even if I hadn’t found the wreckage, the views at The Outlook and the summit of Mt. Success made the hike entirely worth it. I only saw a few other people during my hike and everything was so peaceful and quiet. I could only hear the wind, animals, and the occasional plane flying overhead, ironic as that was.

All this goes without saying and is pretty cliche, but PLEASE:

As always, pack it in and pack it out. Yes that includes toilet paper. Leave it better than you found it. Leave only footprints, take only photographs. Don’t take anything from the wreckage. Don’t build random cairns or move rocks around. Carry your ten essentials. Hydrate! Know when you need to turn around. Know your body and its limits. Tell someone where you’re hiking… Blah, blah, blah. Don’t be THAT guy. 😉

Be safe, be smart, have fun!

Here are some of the best sources I found if you’re interested:

William Peter Carey, Petitioner, v. Civil Aeronautics Board, Respondent, 275 F.2d 518 (1st Cir. 1960)

CAB Accident Investigation Report File No. 1-0226

ICAO Circular 47-AN/42 (180-184)

newenglandaviationhistory.com

aviation-safety.net